A lobster storage facility in Middle West Pubnico, Nova Scotia was set on fire this week following weeks of increasingly violent attacks on Mi’kmaw nation fishers.

Early Wednesday morning, a pair of Mi’kmaq Lobster fishermen were barricaded in the storage facility burned down early on Saturday.

Nova Scotian fishers who work for corporate fisheries in Nova Scotia are upset that Indigenous fishers are continuing to catch lobsters.

There is currently a dispute over the rights of the Mi’kmaq people in the treaty that has been in place for at least 260 years.

The treaty rights were reaffirmed in 1999.

On September 17, 1999 the Supreme Court of Canada acquitted Mi’kmaq Donald Marshall Jr. of three charges relating to federal fishing regulations: selling eels without a license, fishing out of season, and using illegal nets. The SCC accepted his argument that the treaties gave him the right to fish for a living (TAL).

The lobster fishing website, The American Lobster (2002) says,

“The key question arising from [The Marshall Decision] is what the 1760 treaty means today. The treaty gave the Mi’kmaqs the right to trade the products of their hunting, fishing, and gathering for “necessaries”. The Supreme Court of Canada interpreted this to mean the right to earn a “moderate livelihood” through trading fish and game.

The facts are clear. the Mi’kmaw people have a right to fish, and they are fishing lobster responsibly. The counter-argument that there won’t be enough lobster for white fishers when the season comes back is insidious at best. “

“What the Marshall decision confirmed was that Indigenous fishers do not need a commercial fishing license to sell their catch so long as it is for a ‘moderate livelihood’.” said Chirag Patney, a recent graduate of the Rural Planning and Development masters program at the University of Guelph.

He adds, “This, coupled with their inherent right to fish for sustenance (food and money), recognizes that Mi’kmaq peoples can fish throughout the year.”

Earlier this week I did a thing that no one should do…

I looked at the comments on a Facebook post of a National Post article about a van belonging to indigenous fishers that was set on fire on Wednesday.

We all know that internet comments are toxic, but I saw one that made me realize there is a real rift in the way we interpret the issue of treaty rights in Canada.

The comment (on a now-deleted post) said something along the lines of, “I understand both sides of the argument here, the [Ed – white] fishermen just want to make a living.”

I know the person who posted the comment probably didn’t mean it maliciously, but it exposes a real problem in our understanding of national legalese.

We can’t argue for “both sides” in this situation. The conflict right now is about whether Canadians will honour treaties made in the past.

If the answer is “no” then none of our laws should hold any weight and we should expect an announcement that we live in a lawless society imminently.

In this situation, there are clearly defined answers. The Nova Scotian fishermen are wrong. They do not have the right, legally, or ethically to be attacking the Mi’kmaw fishers.

“The rights of Indigenous Peoples are not given to them by treaties or the colonial government,” said Patney. “Rather, those rights are recognized and affirmed through treaties and other things such as Section 35 of the Constitution Act of Canada.” [Ed- “It is important to understand that Section 35 recognizes Aboriginal rights, but did not create them.”]

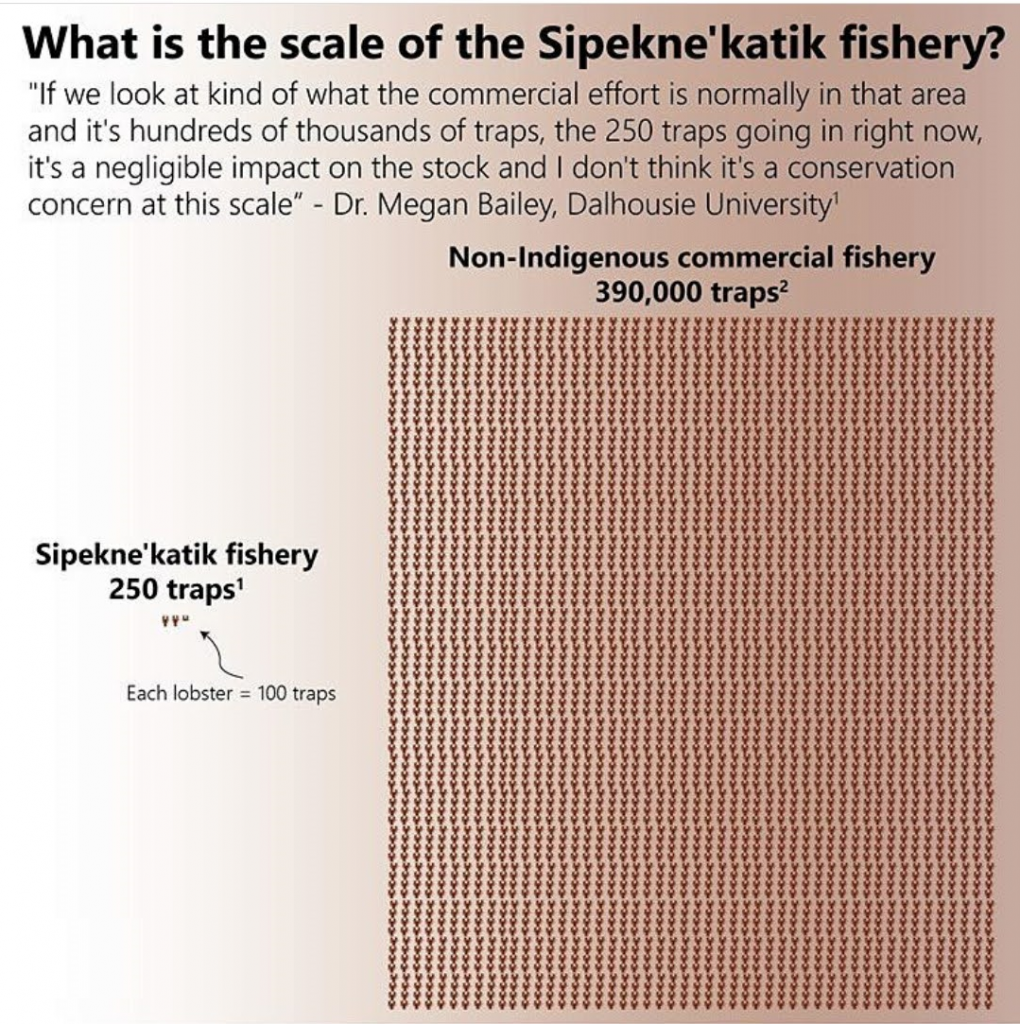

Statistically – if you want to get into it that way – industrial fishing in the province, makes up something like 99.3%, of all lobster taken out of the water. The indigenous fishermen only take up the other 0.7%.

“If we look at kind of what the commercial effort is normally in that area and its hundreds of thousands of traps, the 250 traps going in right now, it’s a negligible impact on the stock and I don’t think it’s a conservation concern at this scale,” said Dr. Megan Bailey from Dalhousie University.

Damning, sure, but that’s all beside the real point of this conversation.

The Mi’kmaq people have a right to the land and the water as long as you still regard our treaties as legally binding.

Treaty rights are technically the same legal rights that allow everybody who’s not indigenous to be on the land and to fish in these waters.

These agreements made hundreds of years ago so often get ignored.

And while you could “both sides” it and say “well I see where everybody’s coming from.” the reality is, if that was true, you would also be capable of seeing that the actions the people setting fires are taking are rooted in racism and anti-indigenous rhetoric.

Sure, most of the Nova Scotian fishers are small-time folks who don’t work when lobster isn’t in season, but their struggles cannot and should not fall on the shoulders of the Mi’kmaw.

Additionally, we can’t forget that most of these angry people are employed by the industrial fishing companies that brought about the collapse of the fishing trade and necessitated national sanctions to prevent the extermination of the product that brings them a livelihood.

If the industrial fisheries aren’t paying the Nova Scotian fishers enough money to live on during the off-season, the workers (fishers) should realize that the fisheries are taking their money and exploiting their labour.

If there is anger to be focused, it should be focused on punching up at the companies, not down at indigenous people.

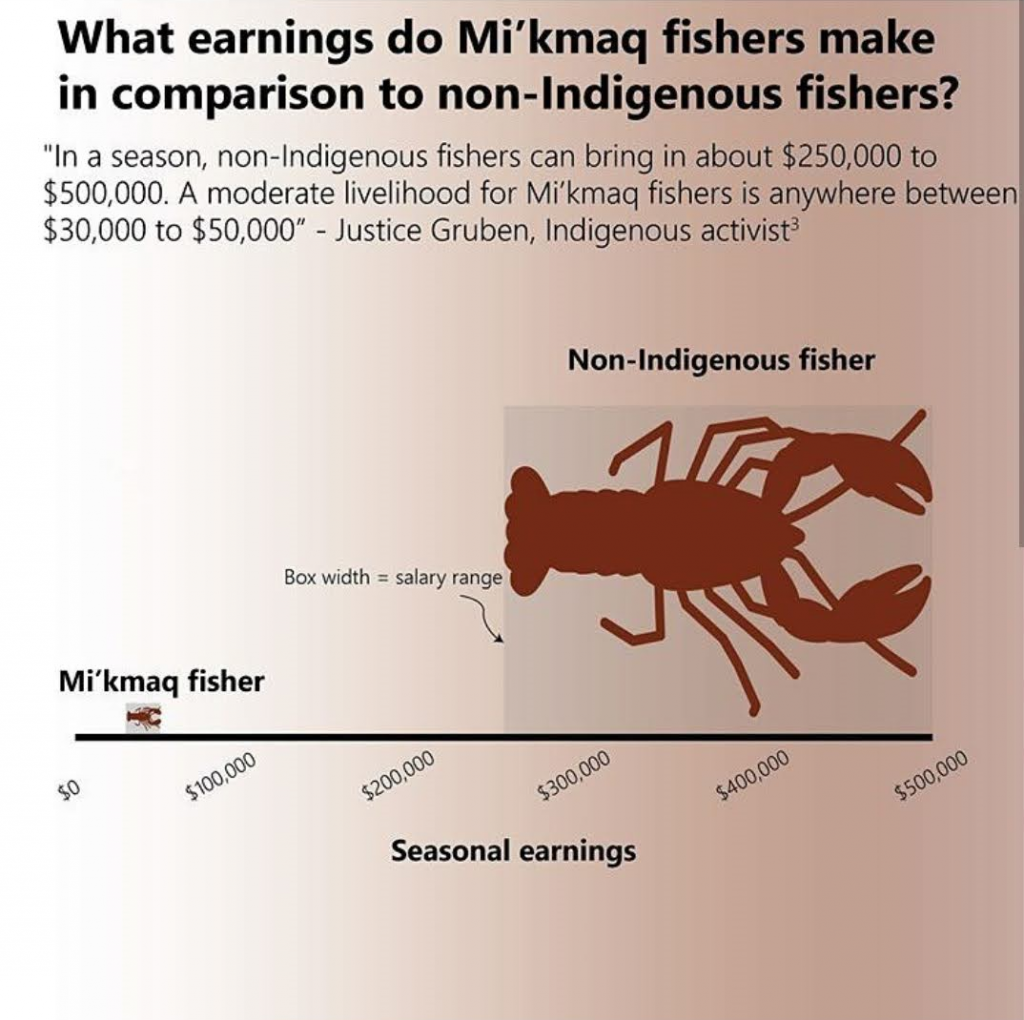

The larger issue we have a hard time talking about in our country is that of wealth disparity.

Wealth disparity is intrinsically linked to racist attacks like this. The rhetoric that ‘indigenous fishers are stealing income from colonial settlers’ is one that is rooted in economic jealousy.

“In a season, non-indigenous fishers can bring in about $250,000 to $500,000. A moderate livelihood for Mi’kmaw fishers is anywhere between $30,000 to $50,000,” said Justice Gruben, an indigenous activist.

[To note: “a moderate livelihood” is what is allowed in the treaty of 1760, and confirmed in 1999. These words are not without meaning.]

The colonial fishers can’t fish right now because the national season is over, but the people who are native to this land should not be, and are not, beholden to the same laws.

I don’t want to see photos of small-time fisheries, being set on fire.

I don’t want to see pictures of boats being set on fire.

I don’t want to see these things any more than I want the RCMP to shoot indigenous people in their homes as they do wellness check-ups (I want this to stop).

Facebook comments saying things like “I understand both sides” and “all lives matter,” are inflammatory phrases that only either belie ignorance or some other form of internal, potentially unrecognized, bigotry.

Treaty rights matter if we hope to have an enforceable legal system in Canada.

Right now it’s looking like laws are optional.

We can’t “both sides” every issue. It’s time to choose the correct side of history.

It’s time to stand with the Mi’kmaw Nation.

You’re so interesting! I don’t believe I’ve truly read through something like that

before. So wonderful to find another person with a few genuine thoughts on this subject matter.

Really.. thanks for starting this up. This website is one thing that is needed on the web, someone with a bit

of originality!