There’s an oft-cited statistic that humans are anywhere from 80% – 95% water. What seems inescapable is that water is an incredibly important part of daily life. People die when they cannot access it.

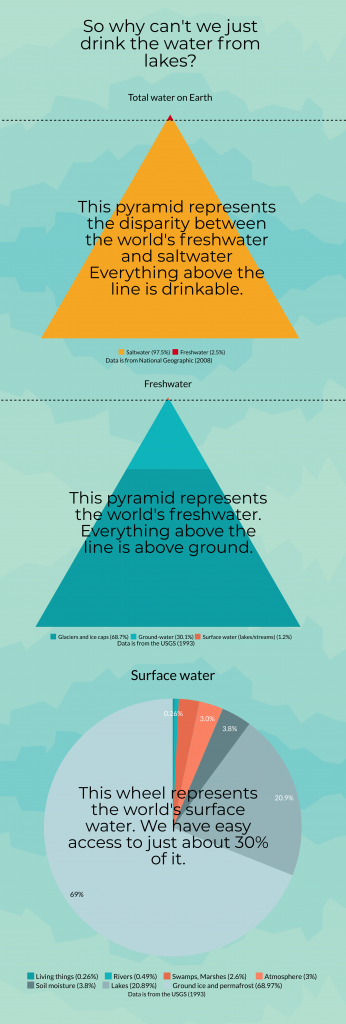

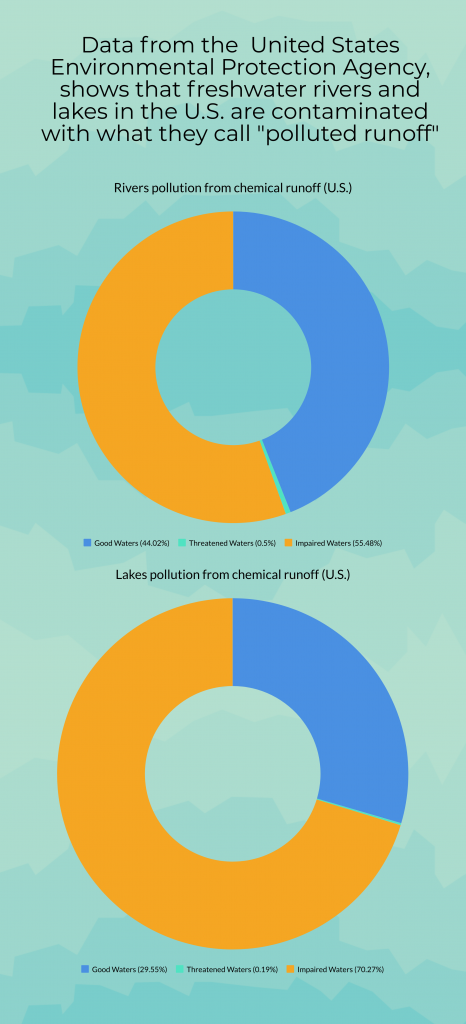

Much of the surface of our planet is covered in water. At first glance, this may seem like a good thing and that water is a resource that will never leave us high and dry. Unfortunately, the vast majority of surface water is undrinkable for one reason or another. Maybe it’s full of contaminated ocean salt, or it’s frozen on one of the poles.

This means there are only a few, relatively rare places fresh, drinkable water can be found. Freshwater rivers and lakes, and groundwater reservoirs.

The question is “how will this affect the future of water?”

For drinkable water, we can split it into two categories:

Renewable and non-renewable

Technically, freshwater is a renewable resource. As water evaporates, it can lose its salination, and as it falls back onto mountains it replenishes the rivers and lakes of freshwater.

However, water purity is highly tied to atmospheric pollution and depending on smog levels and chemicals used for farming, many toxic chemicals end up in rain more often that is healthy (this is part of the reason why you should boil any rainwater you plan to drink).

Many ground-water aquifers are non-renewable water resources and will theoretically be depleted with time.

One example of a groundwater reserve that is a key battleground is in Aberfoyle, Ontario.

Water activists believe that water is a human right since it is one of the only things all humans universally need to survive, but like most other resources, water extraction has been privatized in many places.

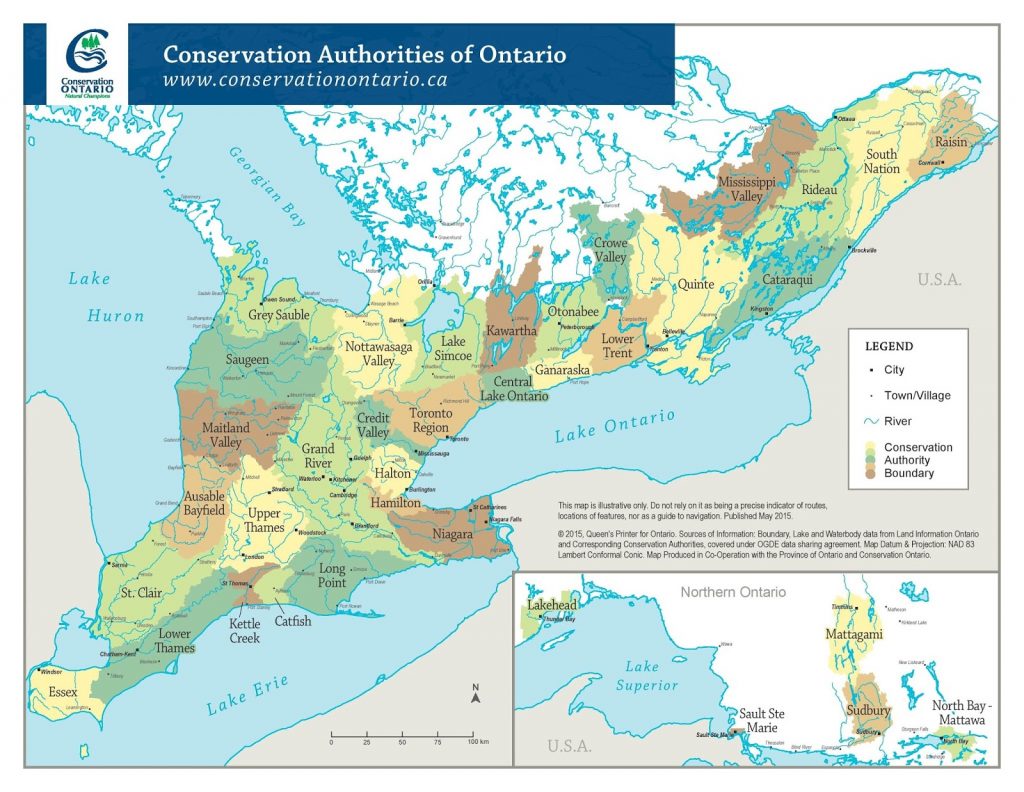

The township of Aberfoyle is in Wellington county. Conflicting municipal jurisdictions give approval of land-resource extraction to the county. In 2000, Wellington county, through the Province of Ontario, leased an underground aquifer to Nestlé. From this bottling facility, Nestlé packages, and distributes bottled water, pop, and La Croix. The jurisdiction of municipalities is separated by “watersheds”

In 2006, when the Nestlé contract was up for renewal, the Province began fielding complaints about Nestlé’s business practice, distribution of the resource, and the amount Nestlé was paying for the water.

“The Ontario government is responsible for issuing ‘Permits to Take Water’.” said former MPP for Guelph, Liz Sandals. “Permits to Take Water are approved only after thorough scientific and technical reviews demonstrate that a water taking will not have adverse effects on the water supply or other water users.”

“The rules for granting a ‘Permit to Take Water’ apply equally to all applicants – agricultural operations, municipalities or Nestlé.” Sandals said in an email. “The overarching criteria is that water taking must be sustainable. In order to ensure sustainability, the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change (MOECC) has ordered the monitoring of the water table in over 25 test wells in the area around Nestlé’s well.”

Sandals added that in times of drought in Ontario, The Grand River Conservation Authority has the authority to order Nestlé to stop pumping the water.

As a final comment, Sandals assured me, in the context of the Guelph chapter of the WWW, that Guelph and Nestlé are in different watershed jurisdictions.

However, based on this image from the Ontario Conservation authority, the statement “Guelph and Nestlé are in different water sheds and do not compete for water.” is visibly untrue.

In an interview with CBC in 2016, Maude Barlow, the head of the Council of Canadians, said “If Nestlé gets the next permit fulfilled, they’re going to be taking over six million liters of water a day from the Grand River watershed”

For years, groups like the Wellington Water Watchers (WWW), have been arguing for a less commodified extraction of water, and a return of local watersheds to community control.

The WWW is a local activist group founded in 2007 when local activists became aware of the Nestlé plant in earnest. Some of their founding members discovered that water being bottled in Aberfoyle could be found everywhere from South America to Europe. The community-minded thinkers in Wellington County and the City of Guelph put together a local advocacy group to contest Nestlé’s claim to the Grand River Watershed.

Kayla Weiler is a member of the WWW community. She got involved with the group during her undergrad at the University of Guelph and is passionate about water for a very personal reason.

Weiler is from Walkerton, Ontario. She was in Kindergarten when the area was hit with a dramatic e-coli outbreak due to mismanagement and underfunding of water filtration systems on the Bruce Peninsula. Weiler was infected with e-coli as a child.

“That dramatic experience that I had when I was five and six years old where, you know, people in my community had gotten sick and seven people died,” said Weiler. “This practice of water use it had affected how I see the water, and it was for a really long time that I was actually very afraid, of water as a kid.”

“Having had that experience, I took that fear and I changed it to advocacy and fighting for water protection,” Weiler added. “It’s taken me from just talking about local water systems, to also having those conversations about how corporations use water and sell it for profit and how water is for the public good, and it’s for communities, not for corporations.”

As a member of the Wellington advocacy group, Weiler is well versed in the local fight, and the push to drive Nestlé out of the area.

“When we see companies like Nestlé as well as other major companies that instigate concerning amounts of water taking.” Weiler said, “What you’re seeing is that they’re taking more than they’re allowed, and can get away with it.”

The conflict between the groups is ongoing, but it is not the only argument of its kind in the world, as bottled water becomes the source of water for countries and states increasingly facing drought, it becomes a business that’s hard to give up.

“There are so many different water advocacy groups, not just seen in the Guelph/Eramosa area but also across Canada and across the World that are fighting for water resources.. I think that we’re going to see more and more people join us in that fight when the conversation about climate change presents new challenges.”

In another area of concern, in the future, groundwater may be the only source of water left to humanity.

Due to rain pollution groundwater is some of the cleanest fresh water left on the planet.

In the future it seems renewable water could go one of two ways.

The first is the continued privatization and cost of renewable water. This will eventually cause a class division among the population of those who can afford access to publicly cleaned water, or private bottled stock, and those who cannot.

We’re already seeing something of this sort with boil water advisories in Canada.

Some of the poorest communities do not have access to publically funded water decontamination facilities, or access to a renewable water source and are forced to boil the water they use for cleaning and drinking.

“I’m somewhat fearful for the future of water in Ontario. There are still a lot of myths that Canada and Ontario have too much water, or we have so much water that we’re fine.”

The other possibility for the future is a de-privatization. A return of all watershed aquifers to public spheres and the legal decommodification of water as a resource.

“There actually was one point in Bolivia where there was a war over water.” Weiler said, “And I think that that’s a scary future and what could happen is we could have, you know, really dramatic conflicts over water because it is such a valuable resource.”

While we can’t know what the future holds, we can make some educated guesses.

Ultimately, we are able to look at trends from the past, compare them to where we are now and look forward to where we will be.

There are some changes we can make in the present that might stop some things from ever happening. As a society, we’ll need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and cut down on the kind of pollution that causes smog to prevent the ice caps from disappearing on us, Continuing to advocate for the public, clean water systems will help preserve the water we have left for future generations, and reduce the commodification of water.

But you knew all of this already, right?